May 28, 2006

DAN SHAPLEY, ENVIRONMENT EDITOR

Fast-growing plant threatens native foliage

Reporting invasive species can help stop it before it gets established locally

By Sharon Pickett

For the Poughkeepsie Journal

As the name of the latest threat to our region's forests and farms implies, the mile-a-minute vine is advancing at an alarming rate.

The mile-a-minute vine can grow up to

15 centimeters a day.

Native to eastern Asia and southeast Asian islands, mile-a-minute vine (Polygonum perfoliatum L.) arrived in the United States in the 1930s via a shipment of rhododendrons to a plant nursery in York County, Pa.

It has spread throughout the mid-Atlantic states, and into New England to the north and Ohio to the West. Prevalent on Long Island and in the lower Hudson Valley, it was recently found in Dutchess County around Wingdale.

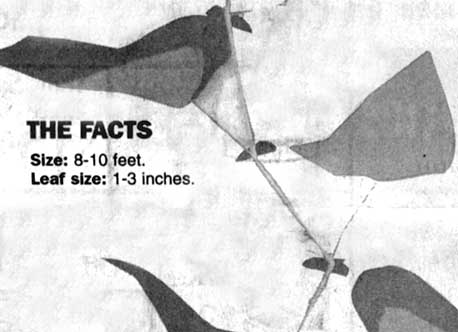

A prickly annual vine, mile-a-minute grows up to 20 feet long as it climbs over plants and structures to reach sunlight. It has pale green triangular leaves and blue berrylike fruit. The vine generally colonizes open areas and proliferates along the edges of woods, wetlands, streams, roads, fences and fields.

What makes this invasive plant so noxious, besides the speed at which it travels, is its ability to out-compete native species. It blankets everything in its path. It threatens plant nurseries, orchards, tree farms, parkland, scenic roads and even forests, since it shades out emerging tree seedlings and species in the understory.

"It has long been believed that non-native invasive species such as mile-a-minute vine are second only to habitat loss as the biggest threat to biological diversity," Meg Wilkinson, the program coordinator and database manager of the Troy-based Invasive Plant Council, said. "When plant diversity is reduced, wildlife species are negatively impacted by diminished food and habitat sources and the entire ecosystem suffers."

Globalization a factor

As globalization facilitates the travel of people and products around the world, more plants, animals and microbes are spreading to new areas.

They can arrive intentionally — perhaps by an over-enthusiastic gardener or collector — or accidentally, as in the case of the zebra mussel, which survived a trip from the Caspian Sea to the Great Lakes in the ballast water of a ship. They can originate as far away as Asia or as close by as another region in the United States.

Not all non-native species are invasive. Corn, wheat, cattle and poultry introduced to the United States are staples of this country's diet. Other species introduced for biological pest control, landscaping, sport and pets have proven to be benign. A small percentage of introduced plants are responsible for an enormous amount of environmental and economic harm.

"It is when a species becomes 'superabundant' that problems arise," Wilkinson said.

Invasives grow virtually anywhere and reproduce quickly. She calls them the "schoolyard bully of the plant world."

Many are local menaces

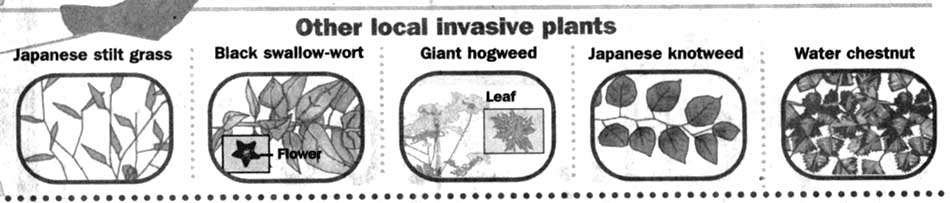

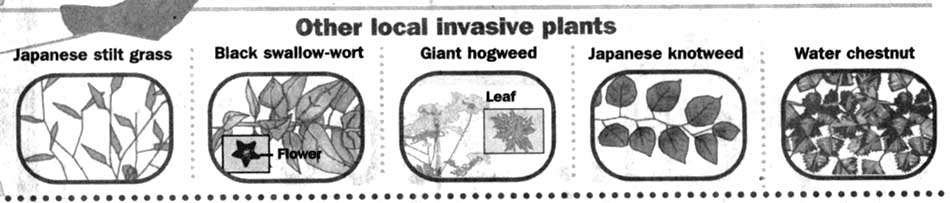

There are many invasive plants of concern in the Hudson Valley, including Oriental bittersweet, purple loosestrife and Japanese knotweed. Because mile-a-minute vine has only recently colonized Dutchess and remains in isolated spots, we have a unique chance to stop its spread. Learning to recognize and report it is the first step.

The New York State Invasive Species Council is coordinating mile-a-minute early detection and rapid response efforts throughout the lower Hudson Valley. This committee consists of public agencies, private organizations and concerned citizens. Its plan includes systematic surveying, mapping, monitoring and eradication of mile-a-minute vine.

"Early detection and rapid response are the best tools to fight the spread of mile-a-minute vine in the Hudson Valley," said Chris Zimmerman, the ecological management coordinator for The Nature Conservancy's Eastern New York Chapter.

The plant has shallow roots, so people can easily pull it up. Seeds, however, can remain viable for up to five years. Because they germinate in the early spring, they get a head start on many native plants. Plants should not be pulled after mid-July, since doing so will help disperse seeds; instead, it's best to gather and boil seeds.

"Repeated, pulling, mowing and trimming will prevent flowering and reduce or eliminate seed production," Zimmerman said, "but many sites will require monitoring to remove new seedlings."

Report Invasions

If you see mile-a-minute vine, report it to the Mile-a-Minute Rapid Response

Team by contacting by contacting Bob Appleholm at the Cornell Cooperative

Extension. He can be reached at:

E-mail: appleholm1@aol.com

Phone: 845-505-7267

Sharon Pickett is a public affairs specialist for the Nature Conservancy's Eastern New York Chapter.

Copyright 2006, Poughkeepsie Journal. Reprinted with Permission.

www.poughkeepsiejournal.com