February 20, 2005

POLLUTION GUIDELINES

Cleanup guidelines lag

Health-risk assessment under review

By Dan Shapley

Poughkeepsie Journal

POLLUTION GUIDELINES

Cleanup guidelines lag

Health-risk assessment under review

By Dan Shapley

Poughkeepsie Journal

People living at polluted sites nationwide could be exposed to the toxin trichloroethylene, or TCE, at levels higher than the Environmental Protection Agency identified as a health concern in 2001, because the EPA never set new cleanup standards based on its study.

The health-risk analysis that identified the danger TCE posed to those who breathe even minute amounts was never translated into EPA policy, despite the recommendation of its own Science Advisory Board. At the prompting of industry and other federal agencies, the EPA has subjected the analysis to a review by the National Academy of Sciences.

That review will take more than a year, leaving those who live at polluted sites and the agencies responsible for remedying them using cleanup guidelines for the ubiquitous solvent that vary from state to state, and even within the boundaries of one town -- East Fishkill in Dutchess County.

Problem not new

Environmental and health agencies have been grappling with vapors that seep in from polluted groundwater into homes since 1990.

If the EPA had set regulations based on its draft health analysis, it would have put national cleanup guidelines between 0.017 to 1.7 micrograms of TCE per cubic liter of air. The EPA can detect TCE at levels of 0.38 and higher.

In East Fishkill, the EPA has committed to removing all TCE vapors it can detect in the Hopewell Precision neighborhood, where groundwater is polluted with TCE.

EPA spokesman James Haklar described this as a "pro-active" approach, determined by aspects specific to that site, that will address homes where there is a "potential impact." It also ultimately saves money because it will reduce long-term monitoring costs.

In the same town, a few miles to the south, the EPA could permit TCE vapors to remain in homes in the Shenandoah neighborhood, as long as they don't exceed New York's guideline of 5 micrograms per cubic liter -- about 13 times higher than the smallest detectable concentration.

Vapors of TCE and/or a related chemical have been detected beneath 14 homes there, and the EPA plans to test inside homes before the end of winter.

The apparent discrepancy is based on conditions specific to the two sites, including that TCE is the main contaminant at the Hopewell Precision site, but a secondary contaminant in the Shenandoah neighborhood, Haklar said.

Some residents, however, are outraged the EPA won't commit to cleaning their air as much as the agency will in their neighbors' homes.

"It's not a case that the danger is not there. It's more a case of whom are we protecting," said Denis Callinan, who lives in Shenandoah. "It's obvious we are protecting the federal government because they are one of the worst polluters ... and we are definitely protecting major industry."

The discrepancies only grow with the miles.

In Endicott, about 180 miles away, New York and IBM Corp. are using the state's guidelines -- though residents there have been outraged since learning of the EPA's goal at the Hopewell Precision site in East Fishkill. Groundwater there is polluted with TCE from an old IBM facility and vapors have seeped into hundreds of homes.

"It is ludicrous to me that there are different standards," said Betty Hicks, whose home in Hopewell Precision is being ventilated to reduce vapors. "People in Appalachia should die, and people in Scarsdale shouldn't die? It's ridiculous."

State and federal elected officials have called for clearer, national standards.

National standards lacking

With the EPA's health-risk analysis in limbo, there are no national standards that dictate when the EPA should take action to clean a site, nor are there national guidelines for how thoroughly sites should be cleaned.

The EPA uses a variety of guidelines, which can vary among the agency's nine regional offices, to determine which sites need to be cleaned, and to what extent.

"EPA is currently evaluating a number of interim approaches for screening levels while awaiting a final TCE risk assessment. Final clean up standards are determined, as always, on a site-specific basis," Henry Longest II, acting administrator for EPA's Office of Research and Development, wrote to U.S. Rep. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., in December, after she requested the EPA finalize its 2001 analysis.

TCE is one of several common halogenated solvents that were used for decades to clean metal parts. Demand dropped in the mid-1980s as health concerns prompted new regulations, but TCE production rebounded in the 1990s after similar chemicals were banned for depleting the Earth's protective ozone layer.

Manufactured by the Dow Chemical Company and PPG Industries Inc., TCE's main use now is as a precursor in the manufacture of refrigerants. North America used about 220 million pounds of TCE last year, according to the Halogenated Solvents Industry Alliance.

TCE is nearly ubiquitous -- present in nearly 60 percent of the nation's 1,430 Superfund sites, and in the air in most urban environments. It vaporizes easily, and can seep from polluted groundwater through soil and into homes -- posing a risk not only to those who drink tainted well water, but also those who breathe the air in their homes.

Three and a half years ago, the EPA released a draft health-risk assessment that weighed the latest scientific evidence about the toxicity of TCE. Following recent National Research Council and presidential guidelines, the analysis was the EPA's first to evaluate the risk the chemical posed to children, and the risk posed by cumulative exposure to other contaminants.

The results were sobering:

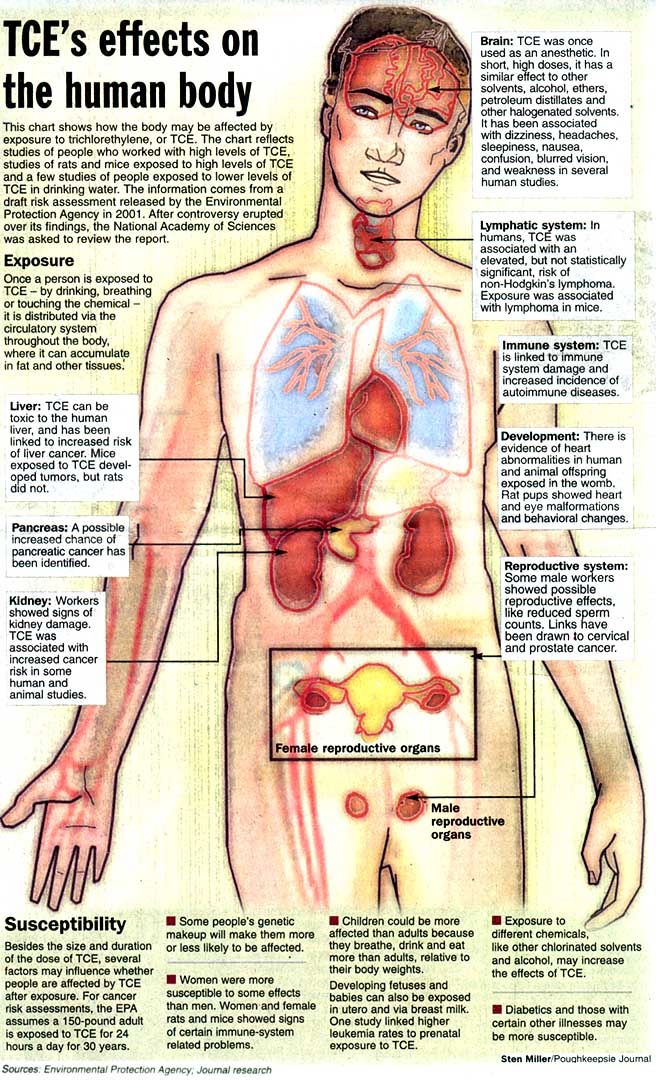

- TCE is far more toxic than thought -- "highly likely" to cause cancer and linked to a variety of toxic effects on the nervous, immune, reproductive and other body systems.

- Breathing TCE was identified as a potent risk, even at very small concentrations.

The EPA normally sets cleanup standards for polluted sites based on risk analyses. The EPA sets its standards to reduce exposure to the point where no more than one in 10,000 adults would be expected to get cancer if a 150-pound adult was exposed for a lifetime -- 24 hours a day for 30 years.

In this case, TCE cleanup standards for contaminated air would have been so low, the most sensitive instruments could not always detect harmful concentrations.

- Some of TCE's toxic effects are likely to be greater on children and adults with certain diseases, including diabetes.

- Effects are likely to be exacerbated by exposure to other chemicals, including alcohol and other chlorinated solvents.

Multiple contaminants found

It's not uncommon to have multiple contaminants at sites, and that's the case in both East Fishkill neighborhoods

Shenandoah is primarily polluted with tetrachloroethylene, or PCE, which was allegedly used to cleanse microchip racks by an IBM Corp. contractor in the 1960s and 1970s. In groundwater, PCE degrades into TCE.

The Hopewell Precision site has the solvent trichloroethane, or TCA, in the water as well as TCE. The EPA believes a metal cabinet manufacturer, Hopewell Precision, used both chemicals to cleanse metal parts.

When the body metabolizes any of the three chemicals -- TCE, PCE or TCA -- the same substance, trichloroacetic acid, is formed, though at different rates for each chemical. Trichloroacetic acid can also form as a byproduct of chlorinating drinking water.

Trichloroacetic acid is the metabolite associated with TCE that is most analyzed for its potential to cause cancer. The EPA's 2001 draft analysis of TCE health risks identified the cumulative exposure to different chemicals as a concern, in part, because of the way they interact when the body metabolizes them.

For Debra and David Hall, that raises questions about the many homes in the Hopewell Precision neighborhood that have detectable levels of TCE and/or TCA, but have not had water filters or ventilation systems installed.

The couple is concerned about health problems they've heard about among people in the neighborhood -- birth defects and cancers, including of the liver and kidney.

David Hall's liver showed unusual enzyme activity, similar to what might be seen in an alcoholic's damaged liver, his doctor told him, yet he has only a handful of drinks every year. They also had two young parakeets die from liver tumors.

"I go every year for the physical. Nothing was ever detected until we moved into this house, and then once they started ventilating, the numbers started to drop," David Hall said.

"I really believe it had something to do with it," Debra said of the contamination. "They say you can't prove it, but that's scary."

No homes in their neighborhood have been outfitted with water filters for TCA, because it did not exceed the federal drinking water standard. New York has installed filters on 14 of the 100 homes where TCA was detected because those 14 exceeded the state's standard. No homes have been ventilated to reduce TCA fumes.

IBM installs filters

In the Shenandoah neighborhood, IBM has installed water filters even in homes that show no contamination, but are near homes that have contaminated water. In the Hopewell Precision neighborhood, however, filters are only installed in homes that have concentrations of either chemical that exceed a state or federal standard.

Because the EPA's 2001 TCE health-risk analysis is still a draft, any cumulative risk posed by multiple contaminants is not considered when the EPA sets cleanup goals at polluted sites.

"It's something that is on the radar of ORD," Haklar said, referring to the Office of Research and Development, "but at this point it doesn't enter decisions."

Industry groups and government agencies questioned the scientific basis for the EPA's risk analysis.

Responding to their concerns, and questions raised by its Science Advisory Board, the EPA joined with the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy and NASA to commission the National Academy of Sciences review. The EPA also convened a symposium a year ago to hear about recently published research.

The National Academy of Sciences review should help settle controversy about the importance of trichloroacetic acid as a human carcinogen, among other issues that led to the EPA's "conservative" risk assessment, said Paul Dugard, science director for the Halogenated Solvents Industry Alliance. The group represents companies that manufacture, distribute and use TCE, PCE and other solvents.

Dugard said occupational exposure studies had not identified clear links to health problems -- though some are cited in the EPA's analysis -- and people with polluted water or air in their homes are exposed to far smaller concentrations than workers were. He also questioned the conclusion humans would have the same health problems identified in lab rats and mice exposed to TCE.

"Most scientists without a green activist edge, if you like, would see the draft report as being extremely conservative in its treatment," Dugard said. "It pushes the acceptable levels down very low. For most people, that's not how they see trichloroethylene. It was widely used and still is used. It's not a super toxin by any means."

The Department of Defense also wanted to see the National Academy of Sciences review the EPA's work.

"We welcome the NAS coming into it," Defense Department spokesman Glenn Flood said. "We want a body like that to be able to stand back from both agencies and say, 'This is what we've got.' "

Both Dugard and Jennifer Sass, a scientist for the Natural Resources Defense Council, said the panel assembled by the National Academy of Sciences seems fair and qualified.

Critics: Cost is issue

That hasn't stopped critics from charging the departments of Defense and Energy are less concerned about sound science than saving money. The federal government is responsible for at least 46 Superfund sites with TCE, many of them at Air Force bases, according to an EPA database. More strict cleanup standards would drive up costs.

The costs can vary, but testing at individual homes often costs $1,000, and ventilation systems can cost between $1,500 to $5,000, according to New York estimates.

"The military has been complaining about this all along. They complained enough that they got it delayed," Sass said. "We know that it's a common, widespread water pollutant. And we know it's very toxic."

This isn't the first EPA risk analysis to get caught in limbo amid controversy, Sass said. The EPA's cancer risk guidelines have yet to be updated.

Based on the agency's 1999 proposed guidelines, TCE would be considered "highly likely" to cause cancer. Under the "current" 1986 guidelines, TCE is considered a "probable human carcinogen."

It will be some time before the EPA finishes its TCE health risk assessment and sets national standards. The National Academy of Sciences panel will convene March 23 and 24. When it completes its 15-month study, the EPA anticipates incorporating it into its health-risk analysis along with recently published research. It will subject the analysis to scientific peer review and public comment.

"We believe this process will not only address the EPA (Science Advisory Board's) comments, but also provide a risk assessment of the highest quality and scientific credibility," the EPA's Longest wrote in December.

New York's Department of Environmental Conservation has identified more than 400 sites statewide that have the potential for vapor intrusion problems with TCE and other chlorinated volatile organic compounds. It is working on a draft policy to test and, if necessary, clean up these sites, most of which had been considered safe until vapor intrusion was identified as a health risk.

The Department of Health is also convening a scientific panel to review its guidelines for TCE in air.

Until there are clear guidelines, people in Endicott, Shenandoah and around the country will continue to worry about their health and know that the longer they are exposed to chemicals -- if they are indeed at unsafe levels -- the greater their risk of developing health problems.

"It is, to me, a tragedy," said Lenny Seigel, who has fought for strict cleanup standards in his Mount View, Calif., neighborhood and around the country. "People are breathing this stuff, so it was a victory for the polluters."

| Watershed Home | Media Menu |