Sunday, July 6, 2003

Stop water polluters now

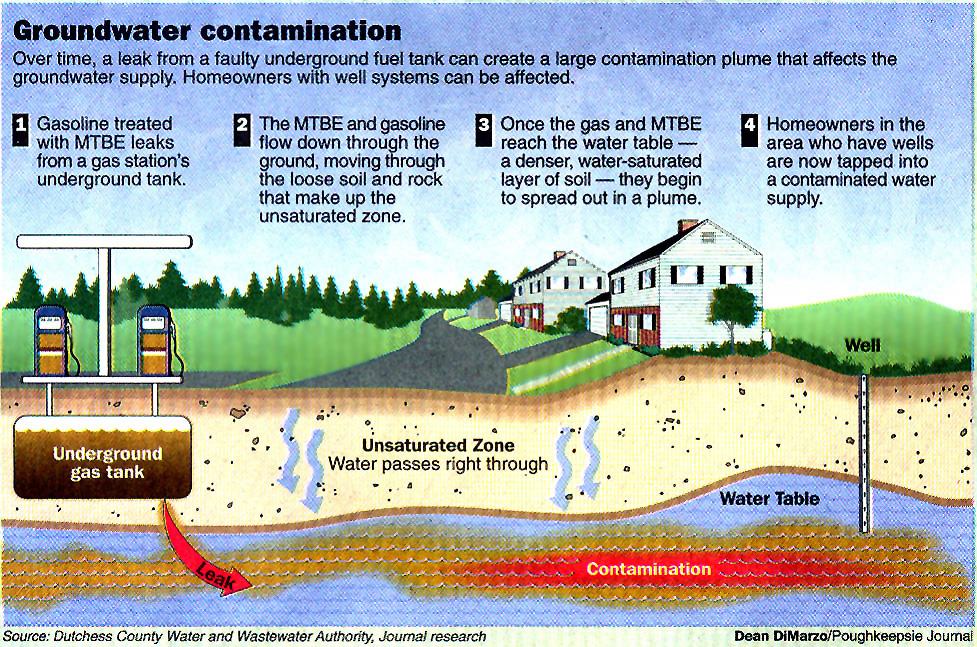

Homes equipped with elaborate, costly filters to catch poisons before they enter water faucets. Gas spills seeping into underground water sources. Development pushing aquifers to the limits of capacity.

It's one of Dutchess County's most confounding challenges: keeping its water safe and clean.

And officials on every level of government aren't doing enough to confront the problem.

Just ask Hyde Park resident Colleen Berrian, who was helping her daughter sell Girl Scout cookies when a neighbor told her homes in their area were plagued by tainted drinking water.

Berrian was furious. She wondered why health officials hadn't informed her about this.

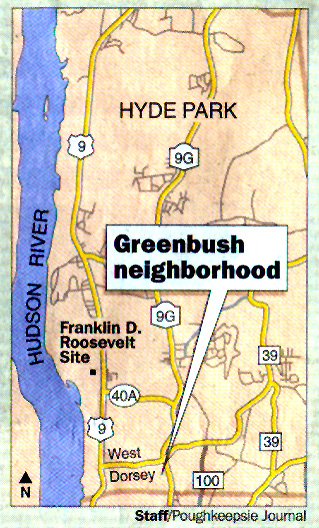

Many troubling questions have been raised since 90 homes in the Greenbush area of Hyde Park wound up with water filters after pollution seeped into their wells from nearby gas stations.

And these questions deserve better answers than officials have been giving. More than that, they must lead to a slew of changes about how groundwater is protected -- and changes in what officials are to do if more spills are discovered in Dutchess.

Several county neighborhoods have become contaminated with potentially hazardous chemicals. In Greenbush, the wells have been polluted with MTBE, or methyl tertiary butyl ether, which is added to gasoline to curb air pollution. Once it leaks, MTBE spreads quickly in groundwater.

If consumed, MTBE can cause cancer or other health problems. Many Greenbush residents are drinking bottled water or go to a water truck the state Department of Environmental Conservation has set up in the neighborhood.

This situation is outrageous, and it's been treated far too complacently by every level of government. These agencies need to get tougher on polluters. And they need to find better solutions to stop these spills from happening.

Stop spills at the source -- The underground storage tanks at gas stations in Dutchess County are not inspected on a regular basis. The state, which handles the permits for these businesses, inspects the sites only if problems are reported. That's not good enough for Westchester and Rockland counties, which have mandated their county health departments to do inspections each year.

Mary Landrigan, a spokeswoman for the Westchester County Department of Health, said, "It's been a very good, successful program. We think we get much more compliance with our regulation."

Samuel Rulli, assistant public health engineer for the Rockland County Department of Health, concurs. Two Rockland health staffers are assigned to do these inspections, and registration fees paid by the gas stations and others using underground storage tanks help fund the program.

"I don't think the DEC could ever get to these facilities on an annual basis like we do," Rulli said.

Statistics bear that out. New York ranks in the bottom third of states in terms of how often they conduct underground tank inspections, according to the General Accounting Office, the independent investigative arm of Congress. Instead, the state relies on issuing citations and fines against the gas stations that have leaky tanks. These are after-the-fact tactics that do nothing to prevent spills.

Free up money for inspections -- In the mid-1980s, the federal government realized it needed to do more to stop water pollution. So it ordered gas storage tank owners to install devices that detect leaks and prevent corrosion. And it gave a generous 1998 deadline for all the changes to be finished before fines were imposed or businesses shut down. State DEC officials say many of the cleanup areas they are dealing with now were identified as a result of this process.

But the GAO also has found a substantial flaw in the law. While Congress created a trust fund -- replenished through a slight gas tax -- to pay for cleanup costs, the money can't be used to help states and localities pay for inspections.

The U.S. Senate has approved legislation sponsored by Sen. Lincoln Chafee, R-R.I., that would improve the 1998 compliance law, in part, by freeing up the trust money for more inspections. That legislation was supported by New York's senators, Hillary Rodham Clinton and Charles Schumer. But New York's congressional delegation still needs to fight to make sure similar legislation is approved by the House of Representatives.

Notify neighbors faster -- Greenbush residents have been highly critical of how the state responded to the spills, raising points that DEC regional director Marc Moran concedes.

While Moran said the state didn't want to panic the community, he acknowledged it should have worked with town officials to get the word out to homeowners, perhaps through an informational letter followed by public meetings.

Moran emphasized how difficult it is to deal with large gasoline spills. Dozens of homes had to be tested. Test results took weeks to come back from the lab. Because the spills didn't come from one source, there was no pattern to them. As a result, of the 90 homes given water filters, about 30 percent of them have not shown a level of contamination above federal safety levels. "But we couldn't take the chance," he said.

Make the polluters pay -- Moran said it is difficult to ascertain who is chiefly responsible for the spills, since ownership of the gas stations has changed hands over the years. State laws essentially say all the gas stations are responsible unless proven otherwise. If the gas stations can't sort it out themselves, the state attorney general's office will, and the penalty payments will go to the state to help fund the cleanup.

The state also has agreed to release $1.3 million toward a $4.3 million project that will bring a public water system to the Greenbush area. About $600,000 more could come through if more Greenbush property owners sign the necessary legal agreements.

Some of the Greenbush residents, including Colleen Berrian, are refusing to sign the agreement because it would limit their right to sue those who polluted their groundwater.

Their reluctance is understandable. The deal is a troubling one. Still, the DEC option might be the best choice available at this point. While the agreement essentially prevents them from suing the state, it does not thwart their efforts to go after the gas stations in court.

Berrian is part of a group that is doing so. They are suing a proverbial "Who's Who" of the oil industry -- British Petroleum, Cenco, Citgo, Exxon and Sunoco. These cases, which seek restitution for property damage and medical and personal expenses, are making their way through the courts.

Many residents understandably bristle at paying $630 per year for a new water system. Some feel they should pay nothing extra for clean water because they didn't cause the water pollution.

But that belies the full story.

MTBE isn't the only reason the Greenbush area needs public water:

- Other forms of pollution -- apparently caused by poorly maintained septic systems in close proximity to those wells -- have been discovered.

- Some of the private wells occasionally run dry.

- A public water system would boost property values.

Greenbush residents are caught in the middle of a mess, and there's no going back. Government and those representing their interests in court should fight like mad to see the polluters pay.

But Greenbush also offers a warning to other Dutchess neighborhoods -- and to the officials who are supposed to be protecting them. Tighter inspections and better notification programs are needed before the next spill occurs in Dutchess County.

Relevant Web links

- To find out more about the state's bulk storage and spill response programs, go to the Web site: www.dec.state.ny.us/website/der/index.html

- To find out more about Westchester County's bulk storage program, go to the Web site: www.westchestergov.com/health/PBS.htm

- To find out more about Rockland County's bulk storage program, go the Web site: www.co.rockland.ny.us/health/default.htm

| Back to index |

| Watershed Home | Media Menu |