August 6, 2006

PRESERVING OUR WETLANDS

Doreen Tignanelli of the Town of Poughkeepsie looks at a pond

around which developers are planning to build homes

Lack of federal, state oversight leaves towns no option but to make own rules

Water: Extent of buffer zones is issue

Story by DAN SHAPLEY

Photo by KARL RABE

Poughkeepsie Journal

Picture a nameless little pond, just under one acre in size, set back in

the woods.

Wildlife like frogs, turtles and ducks might live there. During heavy

rain, it might accumulate water that would otherwise flood nearby

basements or roads.

In Poughkeepsie, the owner of that pond would need a permit — and good

reason — to drain or fill the wetland.

In Pawling, he would have to preserve a 100-foot buffer of undisturbed

plants and trees around a similar pond.

Landowners in many other local towns could do whatever they please to a

pond that size.

In the absence of federal or state laws protecting many small wetlands,

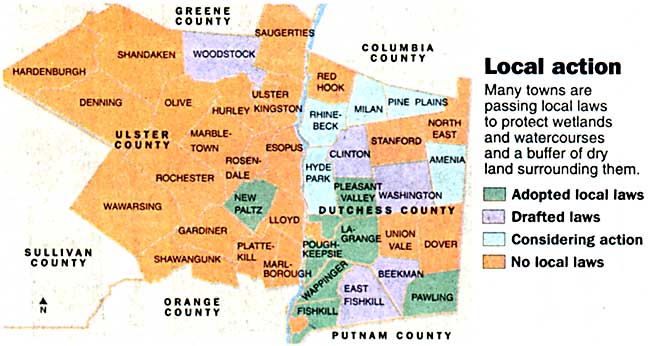

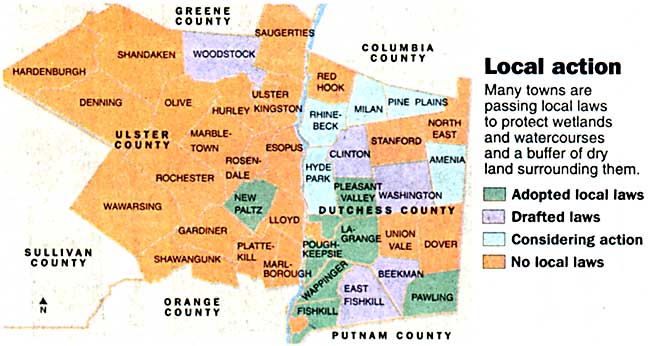

six local towns have passed laws in an attempt to fill the gap.

Five more have drafted laws and five others are in the process of

drafting their own. Others have some zoning restrictions governing

wetlands, or plan to increase protections as they update their master

plans and zoning codes.

No two laws are identical.

Scrutiny varies across region

The patchwork of protection means many small wetlands can be filled,

drained or encroached upon with varying degrees of scrutiny from local

officials charged with looking out for the common good. Because water

doesn't stop flowing at municipal boundaries, upstream towns may be

jeopardizing the water quality of communities downstream.

It also means landowners and developers seeking to alter their

properties face a dizzying variety of local ordinances from one town to

the next.

Landowners have challenged several local laws, claiming they infringed

on their rights to make decisions about — and maximize profit on — their

properties.

In Woodstock, for instance, Wittenberg Sportsman's Club successfully

challenged a wetlands protection law, prompting the town to rewrite it.

"We're looking at filling in regulatory gaps," said Dara Trahan, a

planning specialist for the Woodstock planning board. "We've lost many

of our wetlands that were supposedly national inventory wetlands. Nobody

said boo. ... We've been approving lots that are 50 percent wetlands.

Our hands are kind of tied."

Calls to the hunting club were not returned.

Studies list advantages

Wetlands are ponds, swamps, bogs, fens and other areas where water

accumulates. Studies have documented the way they limit flooding,

cleanse some pollutants, replenish groundwater supplies and provide

habitat for a variety of wildlife.

Since the Clean Water Act of 1972, the federal government has recognized

their importance, and set up a system to protect wetlands across the

nation. Many states, including New York, enacted laws that increased

protection further.

A 2001 Supreme Court decision narrowed the federal government's

jurisdiction over small wetlands, restricting the Army Corps of

Engineers' oversight to wetlands connected to navigable bodies of water.

The decision removed protection for as many as two thirds of the

wetlands in central Dutchess County, according to a Fish and Wildlife

inventory.

A 2006 Supreme Court decision further confused the interpretation of

federal jurisdiction over small wetlands. The Army Corps of Engineers

rarely denies a permit for draining or filling a small wetland, but it

often requires changes to a project to limit the impact.

Since 1975, New York has regulated wetlands of at least 12.4 acres — one

hectare — and a 100-foot buffer surrounding them.

Stuck in Senate

The Assembly passed a bill expanding protection to smaller wetlands this

year. It had the support of Gov. George Pataki, but the Senate

leadership refused to bring it up for a vote.

Environmentalists and, increasingly, waterfowl hunters, have lobbied to

increase protection. New York has lost an estimated 60 percent of its

original wetlands — a figure that is similar to the national percentage.

The loss of any one wetland may affect little, but the loss of many

across the landscape can degrade the quality of groundwater, streams,

creeks and even the Hudson River.

The loss of wetlands, as well as the increased runoff from new roads,

driveways and rooftops, has likely contributed to a measurable decline

in the water quality of formerly pristine Hudson Valley streams in

recent years.

The loss of consistent wetlands protections has come at a time when

development is fast consuming open land in the Hudson Valley, and local

officials say developers increasingly want to build on land with

wetlands and steep slopes.

"We see that more and more in our towns because the developable land —

at least the prime developable land — is taken," said Mike Appolonia, a

councilman in the Town of Clinton, which drafted a wetlands protection

law this summer.

"We're getting now to the types of lands, particularly in Clinton, which

are really undesirable and yet desirable from the standpoint of someone

who wants a house on it."

Population increasing

Of the nearly 80,000 people who moved into the Hudson Valley between

2000 and 2005, 75 percent moved into relatively rural areas outside

established cities and villages.

In Dutchess County, the second-fastest growing county in the Hudson

Valley behind Orange County, 94 percent of the population growth is

dispersed in its more rural areas.

That suburban sprawl may con-sume wetlands, farms and other open spaces,

but the market for new houses has only recently slackened slightly after

five years of explosive growth. People want to buy the houses developers

are building.

Stringent laws sought

Others see restrictive, rigid laws as the only way to preserve wetlands.

In the woods behind Doreen Tignanelli's house in the Town of

Poughkeepsie is a 0.9-acre pond and a larger state-regulated wetland

on the 56-acre former Girl Scout camp, Forest Glen Nature Sanctuary.

The landowner, Harold Buchner, who did not return phone calls last week,

has plans to build as many as 39 homes on his property.

Poughkeepsie's 2003 wetlands protection law struck a compromise

between the desires of environmentalists and builders. A graduated

system requires a greater buffer around larger wetlands, and smaller

buffers around smaller wetlands. At less than an acre, the pond in

Forest Glen requires no buffer.

Tignanelli, member of the town's conservation advisory council, said

that compromise ignored scientific evidence that buffers are needed to

sustain many species. Studies have shown, for instance, that frogs need

substantial forests surrounding the ponds where they breed in order to

survive.

"It's one of the few remaining spots in the Town of Poughkeepsie

that's a refuge for wildlife. It's a sanctuary," she said. "The buffer

sizes are not adequate."

QUOTABLE

WETLANDS PROTECTION

'You have to draw a distinction between regulating and confiscating

land. If something is proposed in the buffer, the applicant would have

to have a pretty good reason to encroach into the buffer to get that

permit.'

Joachim Ansorge

wetlands administrator

LaGrange

'The interesting part is, the (state and federal) laws that are on the

books right now, if you abide by them and go through the appropriate

method of determining what the wetland is, they work.'

John Coutant

Esopus supervisor

'We have a big property rights advocacy in this town, so we're not

pushing the envelope right now. We're pushing education.'

Robert Gallagher

Rosendale supervisor

'We have golf courses in town, so we have to be careful to understand

their need for pesticides. They, on the other hand, have to understand

our needs to protect water.'

John Hickman

East Fishkill supervisor

'If everybody likes this law, I've done a lousy job.'

Frank Marglotta

co-chairman

Milan conservation advisory council

'It's a process, and if you don't have an environmental community group,

like a conservation advisory council, it's hard to create a wetlands law

out of the blue.'

Mary McNamera

coordinator

Sawkill Watershed Alliance

'The town of Red Hook, which has been a model in other areas of open

space preservation, needs to step up to the plate, and resolve itself to

address these smaller bodies of water, and the unequivocal reality that

they are becoming more and more polluted as development marches on.'

Robert McKeon

chairman

Red Hook Farmland and Open Space Committee

'You're looking at three — federal, local and state — three separate

agencies. There's no one-stop shopping, one-stop permitting. That's a

time-consuming issue.'

Tim Villnskis

vice president

Builders Association of the Hudson Valley

'We have the Great Swamp, so we recognize the role wetlands play. ...

We've tried to build in water protection generally into our code.'

Jill Way

Dover supervisor