June 8, 2005

Keeping water under control

Rules shrink pollution, erosion, but are costly

By John Davis

Poughkeepsie Journal

Keeping water under control

Rules shrink pollution, erosion, but are costly

By John Davis

Poughkeepsie Journal

A pounding rain washes across a newly paved parking lot and an adjoining construction site, sending oil, salt and soil down a hillside into a gully and running stream.

After a summer of heavy rainfalls, the stream be-comes polluted — and a neighboring well is threatened by the toxic stormwater discharges.

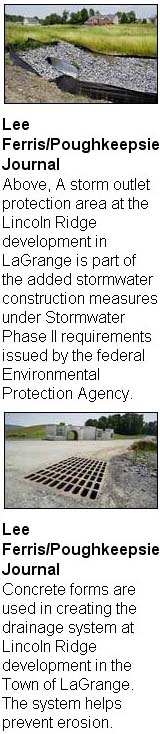

Evolving federal regulations are intended to prevent this scenario from happening to waterways and wells across the country. The Stormwater Phase II requirements are affecting local governments, construction contractors and residents. All must take added measures to reduce soil erosion and polluted stormwater discharges.

"They are ways of trying to address serious runoff pollution problems," said Wendy Rosenbach, spokeswoman for Region 3 of the New York state Department of Environmental Conservation in New Paltz.

While the end result is cleaner water, municipalities and construction firms will be spending more time — and cash — complying.

"This is basically an unfunded mandate — from the EPA to the DEC to the town," said Walter Artus, consulting engineer to the Town of LaGrange. "The good news is we're on schedule. We're making progress."

In 1987, Congress amended the Clean Water Act, requiring the Environmental Protection Agency to regulate stormwater discharges. The EPA in 1990 issued its Phase I requirements, which compel industrial sites and cities with more than 100,000 people to reduce the pollutants from storm sewer systems.

In 1995, the EPA issued Phase II stormwater regulations requiring small municipalities and construction sites larger than an acre to prevent polluted runoff.

The EPA directed the state to implement the new rules. In New York, the DEC in 2003 established a permit system and timetable for cities, towns, villages and contractors.

Municipalities have until 2008 to meet six minimum measures meant to reduce stormwater pollution: public education and outreach, public participation or involvement, illicit discharge detection and elimination, construction site runoff control, post-construction runoff control and pollution prevention and good housekeeping. Each year, an annual progress report must be delivered by June 1 to the DEC.

"As long as you're making progress, they're happy," said Peter Setaro, consulting engineer for the Town of Hyde Park.

Town, city and village engineers across the state recently filed those reports. In LaGrange, a 45-page report was completed by Artus and his firm, Chazen Companies. Supervisor George Wade III said this year's report cost the town $14,000 in extra engineering fees.

Setaro recently completed a 30-page report for Hyde Park. The cost was included in the firm's monthly contract with the town, Setaro said.

The annual reports account for only a portion of costs municipalities bear in meeting the EPA requirements. Issuing permits to builders and monitoring subdivision and building sites during and after construction will require more time and money.

"It impacts the government because it's more manpower," Setaro said. "There is definitely going to be some additional financial burden."

Helping the municipalities in Dutchess County comply with the regulations is the county Soil and Water Conservation District in Millbrook. The district was established by state statute in 1945 to coordinate state and federal conservation programs at the local level. A board of directors hires technical and administrative staff to oversee daily operations.

A state grant of $100,000 is helping the conservation district pay for extra staff time.

For example, the measure of public education about preventing stormwater pollution was met, in part, by handing out literature at the county fair in Rhinebeck in August.

Another DEC measure — identifying illicit discharges — is being met by conservation district staff visiting town highway garages and educating the crews.

"A lot of things, they are already doing," said David Kubek, conservation district technician. "It's just documenting it."

For example, LaGrange has an ordinance prohibiting illegal dumping.

Some emergency measures are no longer permitted. When fire departments pump out flooded basements, they can no longer discharge the water directly into the nearest storm drain.

"The new regulations allow you to put the drain line for a sump pump across the lawn," Hyde Park Highway Superintendent Walt Doyle said.

In the Fishkill Creek watershed, which includes 11 southern Dutchess municipalities, stormwater and construction runoff are two of the top threats to the creek's future health, a report released Monday concluded.

Towns urged to cooperate

The Wappinger Creek Intermunicipal Council, a group of 13 Dutchess municipalities that has set goals to protect the Wappinger Creek, also recognized stormwater runoff as a problem, and encouraged towns to follow the Phase II guidelines.

"It starts off as rainwater, but when it hits pavement and runs off, it's no longer pure. It contains toxic heavy metals and other contaminants," said David Burns, the watershed coordinator for the Dutchess County Environmental Management Council — a county-funded group that advises the county and local governments on environmental issues.

The rules have had a direct impact on developers and builders.

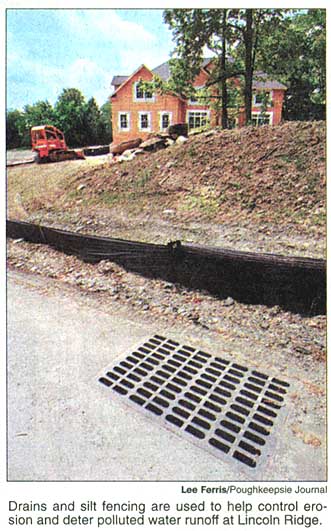

Measures that must be taken during construction to reduce stormwater discharge and erosion — such as constructing silt fences, erecting hay bales, building more detention ponds and monitoring sediment runoff — take time and money.

Michael Meyers, an East Fishkill subdivision builder, said the regulations cost "in excess of $5,000" more per single-family home lot.

"Everybody asks why are costs going up so much," Meyers said of new home sales. "It just gets passed on to the consumer."

After every rainfall of 1 inch or more, contractors must pay a professional engineer to visit the building site to assess erosion impact, Meyers said.

Dealing with another layer of government regulations is taking some builders time to get used to.

"Anytime a new regulation is layered, there's a period of adjustment for both the people impacted and the people enforcing it," Meyers said.

Some are finding that adjustment difficult.

"These regulations are becoming overly burdensome," said Mario Johnson, spokesman for the Builders Association of the Hudson Valley. "The cost is measured in delays." About 100 of the builders in the association have fired off letters to EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson in Washington to vent their displeasure over the added layer of regulations.

"What the builders are saying is there is a lot of overlap," Johnson said.

The designers of the new homes are also spending more time on the job — in this case at the drawing board.

"It's incredible," said Peter Andros, a professional engineer living in Hyde Park. "From a design perspective, it doubles the cost."

Andros estimates construction costs can be increased as much as a third. Fellow engineer Setaro said he thought those estimates were high, saying design cost can increase by 50 to 75 percent.

Whatever the costs, the EPA rules, Andros said, are a predictable reaction to the practices of the few unscrupulous developers who cut corners to save costs — leading to ravaged construction sites, sediment-choked streams and flooded basements.

"They're just a knee-jerk reaction to what developers have done in the past," Andros said. "When you see some of the horror stories, the developers only have themselves to blame."