April 6, 2005

FISHKILL CREEK: REMOVING BARRIERS

Study is planned on impact of dams

Program aims to aid fish movement, restore free flow

by Dan Shapley

Poughkeepsie Journal

FISHKILL CREEK: REMOVING BARRIERS

Study is planned on impact of dams

Program aims to aid fish movement, restore free flow

by Dan Shapley

Poughkeepsie Journal

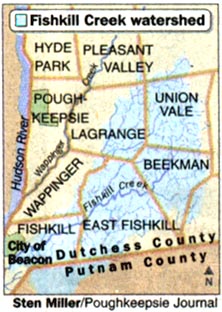

NEWBURGH -- New York will study the dams and other barriers in the Fishkill Creek this year as it looks to remove or bypass structures that harm fish.

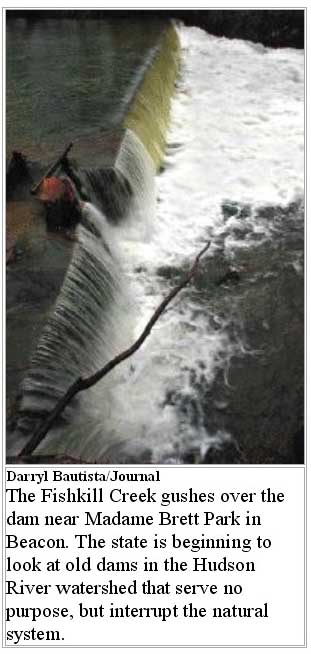

Dams interrupt the natural flow of nutrients, sediment and oxygen downstream. They can heat water to levels unhealthy for trout and prevent fish from moving throughout a stream.

In the Hudson River, they can prevent ocean-dwelling shad and herring from reaching spawning areas, including in the Rondout Creek in Kingston. Some culverts also prevent fish from moving naturally.

About 25 people attended a Hudson River Estuary Program meeting in the Town of Newburgh last week to discuss removing or bypassing barriers in streams.

There are at least 357 dams in the Hudson River watershed, including 196 the state has classified as "low hazard." That means they pose little or no risk downstream if a flood suddenly breaches them.

Many date back a century when mills and factories ran on water power, but now many are in disrepair and serve no useful purpose.

Most dams are in private ownership, though owners are often unaware they are liable for the structures' safety.

The state has no intention of ordering dams to be removed for ecological reasons, said Scott Cuppett, the watershed coordinator for the Hudson River Estuary Program. It hopes to work with dam owners and local groups to identify decrepit dams that serve no useful function that may be removed or bypassed to improve habitat.

Involving people

"We're trying to build a critical mass of people thinking about this," Cuppett said. "This is only one of many tools to restore the watershed ... but this is an important one."

The program has a goal of restoring free-flowing conditions to more stretches of streams in the estuary's 13,390-square mile watershed by 2010.

To that end, Jesse Sayles, a river restoration analyst for the program, will spend this year creating an inventory of barriers in streams to define which would benefit from removal or a bypass like a fish ladder.

His first stop will be the Fishkill Creek, where a citizen's group, the Fishkill Creek Watershed Committee, has identified at least 26 dams. The first dam removed, partially breached or bypassed will not necessarily be on the Fishkill Creek.

"We need a baseline of data before we can think about barrier removal," Sayles said.

Removing dams can be costly, but there are several state, federal or private grant programs.

The only dam removed in New York for ecological reasons cost $2.2 million. The Cuddebackville dam on the Neversink River in Orange County was removed in October by the Nature Conservancy and the Army Corps of Engineers.

The purpose was to invite shad, eels, lamprey and other fish to migrate further upstream, and to expand habitat for endangered and threatened mussels like the dwarf wedge mussel.

Removal costs estimated

Most dam removal projects cost less -- between $30,000 and $1.3 million -- said Dan Kwasnowski, an environmental specialist with a consulting firm, Devine Tarbell & Associates.

Removing dams can also be controversial and, if not done responsibly, harmful.

People fish near dams and enjoy the pools that form behind them. Those swimming and fishing holes are lost when the stream's natural flow returns.

Some also have historic value, like the Eddyville Dam that blocks the Rondout Creek, which is the first lock in the Delaware and Hudson Canal system.

Sediment can be trapped

Dams also trap sediment that is often contaminated. The 1973 removal of the Fort Edward dam, 40 miles north of Albany, allowed PCBs to contaminate a wide swath.

Thirty years later, the Environmental Protection Agency ordered a $500 million dredging project supposed to start next year. The project aims to remove the toxic pollutant from the mud between Fort Edward and the next dam downstream, in Troy.

Dams on the Fishkill Creek in Beacon and Quassaic Creek in Newburgh are among those believed to hold back contaminants like toxic heavy metals.

Experts in dam removal said removing dams, and if necessary the contaminated sediment behind them, is preferable to leaving decrepit dams in place.

Without regular maintenance, dams will eventually crumble on their own, said Dan Miller, the estuary program's habitat restoration coordinator. When they do, the contaminated sediment will be released.

It's better to be proactive and remove the contaminants and dam together, he said.

"We want systems we don't have to maintain," he said. "Our goal is to get to a sustainable system sooner, rather than later."

| Watershed Home | Media Menu |