Trees Along Streams

By Rick Oestrike

Trees Along Streams

By Rick Oestrike

As suburban sprawl spreads across the Hudson Valley, more and more natural streamside vegetation is cut down and replaced with lawns. This is very unfortunate because trees, shrubs and other natural vegetation along streams provide many important benefits including the creation of aquatic and terrestrial habitats, the reduction of floods, the decrease of certain water pollutants and the reduction of erosion.

A common way of reconciling human land uses and the health of a watershed is to create streamside buffer zones of native trees and shrubs. These buffer zones not only separate the harmful effects of human activities from nearby streams but also neutralize many of the harmful effects.

How Streams Benefit from Trees

Dead trees and shrubs that fall into a stream provide food for some aquatic organisms and habitats for others. Tree canopy helps to maintain the cool water temperature in the summer needed by cold-water species such as trout. The vegetation also provides habitats for birds and small mammals.

The strong roots of trees greatly slow erosion of streambanks, and flooding is reduced in several ways. First, some stormwater runoff is absorbed by the roots of trees and shrubs and therefore less reaches the streams. Second, the layer of decaying plant material on the ground in forested areas acts like a sponge that greatly slows the movement of stormwater runoff toward nearby streams. Thus the peak flow of the flood is reduced.

The slowing of stormwater runoff also causes sediment that it carries — such as silt, sand or clay — to be deposited on the forest floor before it reaches the stream. Since some pollutants including phosphate and many heavy metals often adhere to sediment particles, their deposit prevents them from reaching the streams. The roots of streamside trees and shrubs also remove nitrate, another common pollutant, from water migrating toward streams. Streamside forests can also provide a pathway for the migration of animals through populated areas.

Protecting Streamside Vegetation

In recent years many local municipalities have considered passing laws to protect streamside vegetation by creating mandatory buffer zones. One stumbling block has been the question of the proper width of the buffer zone, a topic that has been argued at length. The simple answer is "the wider the better" as far as benefits are concerned. Unfortunately, this concept doesn't translate well into the wording of laws or ordinances. Usually laws will specify a minimum buffer width on each side of the stream.

So, what minimum width is correct? It depends which benefits you wish to preserve. If the only concern is protecting streambanks from erosion then a 30-foot-wide buffer is adequate. However, to preserve corridors for the migration of terrestrial animals, a buffer width of 300 feet or more is appropriate. If the buffer is to help reduce flooding along streams, a width of at least 200 feet is best. The wider the buffer, the more benefits are preserved. Since laws often try to balance the desires of property owners with environmental concerns, the most common buffer width protected nationwide is 100 feet.

Many areas of streamside forest in the Hudson Valley have been reduced or eliminated because of human activities. As a result flooding of streams has increased, habitats have been destroyed and pollutants in stream water have increased. Many property owners resist the creation of regulations creating minimum buffer widths by claiming that they have the legal "right" to do whatever they want on their own property. This is false. While legal property rights do exist, they do not include the right to wantonly damage other people's property. By damaging a streamside buffer, a property owner automatically degrades the stream and increases flooding on properties downstream, thereby causing harm to those other properties.

Other threats to native streamside vegetation include aggressive invasive species such as Japanese knotweed and mile-a-minute vine. Both spread quickly along streams and kill the native vegetation, thus reducing the benefits mentioned earlier. Mile-a-minute vine produces small blue berries that can float downstream for miles before finding a place to grow. Fragments of a Japanese knotweed plant washed downstream can sometimes take root and start a new colony.

Since neither of these plants has strong enough roots to protect streambanks during spring flood events, erosion often increases greatly when they are present. Unfortunately, both plants, and many others, are spreading throughout the Hudson Valley. Statewide and regional efforts to remove infestations before they become well established are badly needed.

Spreading "Trees for Tribs"

There is some good news, however. About four years ago Lou Sebesta, an Urban Forester working for NYSDEC, had the idea to begin replanting damaged streamside buffer zones. He approached the Fishkill Creek Watershed Committee (FCWC) with the idea and it was received enthusiastically. He then requested native shrub seedlings from the Saratoga Tree Nursery and in the spring of 2005 distributed several hundred to a handful of local organizations for planting along streambanks. The effort was so successful that the following spring, he extended the program to more organizations. Its impressive achievements were quickly noticed, and soon the Hudson River Estuary Program of the NYSDEC greatly expanded the effort through a new initiative called "Trees For Tribs" administered by Kevin Grieser.

"Trees For Tribs" supplies seedlings and saplings of shrubs and trees in the spring and fall. It offers free native species for qualifying projects in the Hudson River Estuary watershed within New York State from the Verrazano Narrows Bridge to the Troy Dam. Typical applicants include non-profit watershed groups, land trusts, environmental organizations, municipalities, specialty farmers and home owners.

This program is a key component of the Hudson River Estuary Action Agenda's goal of "By 2015, protect and restore 750 miles of forest buffers through cooperative partnerships and local land use strategies to protect habitat, reduce flooding damage, and cleanse stormwater runoff".

Site analysis and evaluation of the feasibility of a proposed project is available. Groups interested in participating in the "Trees For Tribs" initiative or learning more can contact Kevin Grieser at kagriese@gw.dec.state.ny.us

Other efforts to replant damaged streamside areas also exist, including some Trout Unlimited chapters. Lou Sebesta continues to encourage the planting of seedlings. Plants can be purchased from local nurseries, the Saratoga Tree Nursery, or through local Soil and Water Conservation Districts.

If you have a stream on your property, protect the trees along it, or plant them if needed.

In the summer of 2007, mile-a-minute vine was discovered along Jackson Creek in the Town of LaGrange Park. The photo (at left), from the park, shows its distinctive triangular leaves. A survey in October 2007 determined it had already spread several miles along the creek.

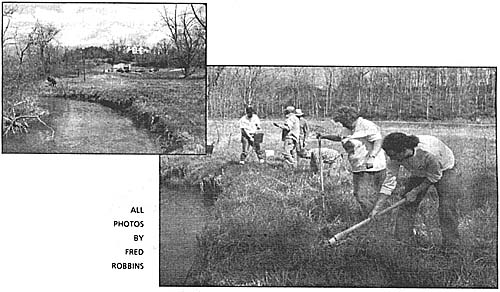

In 2004 a survey by the FCWC determined the large property (at right) along the Fishkill Creek (now owned by the Dutchess County Water and Wastewater Authority) was in need of streamside plantings.

Members of the FCWC (at right) planted native shrubs on the property along the creek in the spring of 2005. From left to right are Dave Burns, Lou Sebesta, Rick Oestrike, Dave Foord, Sonja Sjoholm-deHaas and Ryan Palmer.

| Watershed Home | Media Menu |